Even though language is always evolving, the words we use matter. Having a shared basic understanding of complex terms and ideas can fuel your advocacy and connect others to the issues you care about most. Young people with disabilities from around the world contributed to the creation and design of the glossary. Young people with disabilities have a powerful voice and need to be heard. We are thankful for their insight and contributions. Thank you to Disability Rights Fund for supporting the development of these materials. Original illustrations were created by Ritika Gupta, @artistic._license.

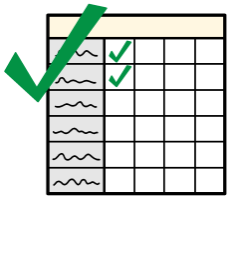

Capacity

Capacity generally refers to a person’s ability to understand the pros, cons, and alternatives to a decision, as well as their ability to communicate their decision. It is specific to every question and every decision, so capacity should be considered at every step of a decision.

When it comes to healthcare decisions, everyone has the right to provide informed consent for their healthcare decisions. Capacity to consent to treatment should be assessed and documented for each treatment or plan of treatment. An individual is presumed to have capacity to make a healthcare decision, to give or revoke an advance directive, and to designate or disqualify a surrogate”.

When it comes to healthcare decisions, everyone has the right to provide informed consent for their healthcare decisions. Capacity to consent to treatment should be assessed and documented for each treatment or plan of treatment. An individual is presumed to have capacity to make a healthcare decision, to give or revoke an advance directive, and to designate or disqualify a surrogate”.

Legal capacity refers to the right of people with disabilities to recognition everywhere as people before the law.

Mental capacity and legal capacity are not the same things. However, the two are often conflated, and thus a person is assumed to lack legal capacity because of a mental or intellectual disability. Such an assumption is discrimination and a violation of Article 12 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Source:

Vanderbilt Kennedy Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities, Informed Consent in Adults with Intellectual or Developmental Disabilities, Health Care for Adults with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: Toolkit for Primary Care Providers (2017), http://vkc.mc.vanderbilt.edu/etoolkit/general-issues/informed-consent/

Gender-Based Violence (GBV)

Gender-based violence (GBV) refers to acts of or threats of violence that are perpetrated against people on the basis of their gender or their perceived gender. GBV can refer to acts that “results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or mental harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.”

Gender-based violence can take a variety of forms—physical, emotional, psychological, sexual, economic—and can include violence perpetrated by intimate partners, family members, caregivers, medical or other service providers, law enforcement, military personnel, educators, employers, and strangers. This violence can be against women and girls, who are and have historically been victimized by harmful gender roles. It can also be experienced by people of gender minorities, such as transgender, nonbinary, and gender nonconforming persons and men, if the violence is motivated by “socially ascribed (i.e. gender) differences between males and females.”

Women and girls with disabilities, who make up almost one-fifth of the world’s population of women, are at least two to three times more likely than women without disabilities to experience gender-based violence in various spheres. They are also likely to experience abuse over a longer period of time, resulting in more severe injuries. Women with disabilities experience both the same forms of gender-based violence, as well as unique forms as a result of their disability; they also experience distinct barriers to escaping such violence and seeking justice.

For more information, check out:

Sources:

World Health Organization, Health Topics: Violence against Women, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

See Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women, Art. 2. G.A. Res. 48/104, U.N. Doc. A/RES/48/104 (Dec. 20, 1993).

Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), Guidelines for Integrating Gender-based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Action: Reducing Risk, Promoting Resilience and Aiding Recovery 322 (Aug. 2015), https:// interagencystandingcommittee. org/system/files/2015-iasc-gender-based-violence-guidelines_lo-res.pdf

World Health Organization (WHO) and World Bank, World Report on Disability 28 (2011).

United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Untied States Strategy to Prevent and Respond to Gender-based Violence Globally 7 (Aug. 10, 2012), http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/196468.pdf. It is worth noting that no global data exists on the incidence of such violence, and studies draw on different sources of data.

Rashida Manjoo, Report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences: women with disabilities, para. 31, U.N. Doc. A/67/227 (Aug. 3, 2012).

Informed Consent

Informed consent is the process of communication between a service provider and a service recipient that results in the service recipient providing consent voluntarily and without threats, intimidation, or inducements, for a service, referral, or dissemination of the person’s private information. The service recipient must receive counselling about the services available and potential alternatives in a language and form that is understandable to the service recipient.

Source:

See International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), Ethical Issues in Obstetrics and Gynecology by the FIGO Committee for the Study of Ethical Aspects of Human Reproduction and Women’s Health 15 (Oct. 2012), http:// www.figo.org/sites/default/ files/uploads/wg-publications/ ethics/English%20Ethical%20 Issues%20in%20Obstetrics%20 and%20Gynecology.pdf

Legal Capacity

Legal capacity refers to the right of people with disabilities to recognition everywhere as people before the law. Under international human rights law, people with disabilities have a right to legal capacity—which is distinct and independent from mental capacity—on an equal basis with individuals without disabilities. Supported decision-making mechanisms may be necessary to empower people with disabilities to exercise their right to legal capacity.

Source:

See CRPD Committee, General Comment No. 1 (2014) Article 12: Equality Recognition Before the Law, para. 39, U.N. Doc. CRPD/C/GC/1 (May 19, 2014).

Person with a Disability

Person with a disability refers to a “person who has some type of physical, intellectual, mental, cognitive or sensory impairment that in interaction with various barriers may hinder his or her full participation in society on an equal basis with others”

This is person-first language that has been adopted by the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. However, many people prefer identity-first language (i.e. disabled person). How people choose to describe themselves – either using person-first or identity-first language – must be respected.

Source:

Psychological Violence

Psychological violence refers to behaviour that is controlling, isolating, humiliating or embarrassing and which causes the person upon who it is perpetrated psychological distress.

Source:

U.N. Secretary-General, In-depth Study on All Forms of Violence Against Women: Report of the Secretary General, para.113, U.N. Doc.A/61/122/Add.1 (July 6, 2006), https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N06/419/74/PDF/N0641974.pdf?OpenElement

Reasonable Accommodations

Reasonable accommodations are defined by the CRPD as “necessary and appropriate modification and adjustments not imposing a disproportionate or undue burden, where needed in a particular case, to ensure to people with disabilities the enjoyment or exercise on an equal basis with others of all human rights and fundamental freedoms”

Examples of reasonable accommodations are extra time to take a test or extended time for a doctor’s visit; permission to bring your service animal to a location where animals are not usually allowed; funding for a support person to travel with you to a conference.

Source:

Reproductive Health

Reproductive health is “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, in all matters relating to the reproductive system and to its functions and processes. Reproductive health therefore implies that people are able to have a satisfying and safe sex life and that they have the capability to reproduce and the freedom to decide if, when and how often to do so.”

For people with disabilities, this means to be free from forced sterilization, forced contraceptives, and forced abortion; to have access to accessible information about reproductive health and safe, effective, affordable, and acceptable methods of family planning, and maternal and newborn health services.

For more information, check out:

Source:

Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development, para. 7.2 U.N. Doc. A/ CONF.171/13/Rev.1 (Sept. 5-13, 1994)

Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR)

Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR): This is a commonly used acronym that refers to both freedoms, such as the freedom to make decisions about whether and when to reproduce free from coercion or violence, and entitlements, such as access to the full range of essential SRHR services. These rights are protected for all people – including people with disabilities – by numerous fundamental human rights treaties, national laws, and policies.

A key underpinning of the right to health— and accordingly, the right to sexual and reproductive health—is the obligation that health-related information, goods, and services be available; accessible; acceptable; and of good quality, collectively known as the AAAQ framework. The AAAQ framework describes the requirements for services that States must abide to fulfil their obligations to respect, protect, and fulfil SRHR. People with disabilities are just as likely to be sexually active and have the same sexual and reproductive health needs as people without disabilities. However, due to multiple and intersecting forms of discrimination on the basis of gender and disability, people with disabilities face unique and pervasive barriers to full realization of their sexual and reproductive health and rights.

Fundamental SRHR services that people—with and without disabilities—should have access to in order to realize their SRHR fully include comprehensive sexuality education; information, goods, and services for the full range of modern contraceptive methods, including emergency contraception; maternal/newborn healthcare (including antenatal care, skilled attendance at delivery, emergency obstetric care, post-partum care, and newborn care); prevention, diagnosis, and treatment for sexual and reproductive health issues (e.g. sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, syphilis, and HPV, cancers of the reproductive system and breast cancer, and infertility); safe and accessible abortion, where it is not against the law; and post-abortion care to treat complications from unsafe abortion.

For more information, check out:

Sources:

Committee on the Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ESCR Committee), General Comment No. 14: The Right to the Highest Attainable Standards of Health (Art. 12), para. 29, U.N. Doc. E/C.12/2000/4 (Aug. 11, 2000). See also Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development, para. 8.3, U.N. Doc. A/ CONF.171/13/Rev.1 (Sept. 5-13, 1994).

Committee on the Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ESCR Committee), General Comment No. 14: The Right to the Highest Attainable Standards of Health (Art. 12), para. 12, U.N. Doc. E/C.12/2000/4 (Aug. 11, 2000) [

International Women’s Health Coalition, Sexual & Reproductive Health & Rights: What Does an Essential Package of Policies and Programs Look Like? (April 2012), https://iwhc.org/wp-content/ uploads/2013/11/essential-package-sexual-reproductive-health-rights.pdf

Sexual and Reproductive Rights

Sexual and Reproductive Rights include the rights to:

- complete physical, mental, and social wellbeing in all matters relating to their reproductive system;

- a satisfying and safe sex life; and

- the freedom to decide if, when, and how often to reproduce.

A range of fundamental rights protected in national laws, international laws, and international human rights documents underpin the right of people with disabilities to decide freely and responsibly on the number, spacing, and timing of their children and to have accessible information and means to do so, and the right to attain the highest standard of sexual and reproductive health. [iii] People with disabilities, as with all rights-holders, must be free to make these decisions free of discrimination, coercion, or violence.[iv] These rights are protected in a number of international and regional human rights documents, including the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). These include the rights to:

- Life

- Health, including sexual and reproductive health

- Privacy, liberty, and security of the person, and to decide the number and spacing of children

- Information and education, including information and education on sexual and reproductive health

- Equality and non-discrimination

- Accessibility

For more information, check out WEI’S Fact Sheet: Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights of Women and Girls with Disabilities

Sources:

UNFPA, Danish Institute for Human Rights, and UN Office for the High Commissioner on Human Rights, Reproductive Rights are Human Rights: A Handbook for National Human Rights Institutions, HR/PUB/14/16, 18 2014).

See Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development, para. 7.3 U.N. Doc. A/ CONF.171/13/Rev.1 (Sept. 5-13, 1994)

CRPD, supra note 671, art. 23(1).

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), Art. 6; Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), Art. 10; Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), Art. 6; African Charter on Human and People’s Rights (African Charter), Art. 4; Protocol to the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (Maputo Protocol), Art. 4; American Convention on Human Rights (American Convention), Art. 4; European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), Art. 2.

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), Art. 12; CRPD, Art. 25; Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), Art. 12; CRC, Art. 24; African Charter, Art. 16; Maputo Protocol, Art. 14; Additional Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights in the Area of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (Protocol of San Salvador), Art. 10; European Social Charter, Art. 11.

ICCPR, Arts. 9, 17; CRPD, Arts. 14, 22-23; CEDAW, Art. 16; CRC, Art. 16; African Charter, Art. 6; Maputo Protocol, Arts.4, 14; American Convention, Arts. 7, 11; ECHR, Arts. 5, 8.

ICESCR, Art. 13; CRPD, Arts. 23, 24; CEDAW, Art. 10; CRC, Arts. 13, 17, & 28; African Charter, Arts. 9, 17; Maputo Protocol, Art. 14; Protocol of San Salvador, Arts. 10, 13; European Social Charter, Art. 11.

ICCPR, Art. 2; ICESCR, Art. 2; CRPD, Arts. 5-7; CEDAW, Arts. 1, 3; CRC, Arts. 2, 5; African Charter, Arts. 2-3; Maputo Protocol, Art. 8; American Convention, Arts. 1, 24; Protocol of San Salvador, Art. 3; ECHR, Art. 14.

Sexual Health

Sexual health is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity. Sexual health requires a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships, as well as the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination and violence. For sexual health to be attained and maintained, the sexual rights of all persons must be respected, protected and fulfilled”.

For more information, check out:

Source:

Sexual and Reproductive Health: Defining Sexual Health, WHO (2017), http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/sexual_health/sh_definitions/en/

Sexual Violence

Sexual violence refers to abusive sexual contact, making a person engage in a sexual act without consent, and attempted or completed sex acts with a person who is unable to consent to sexual contact.

It can take many forms, including any unintended or non-consensual sexual act, sexual harassment, and violent acts. A person may be unable to consent due to their disability (however, having a disability does not mean a person is automatically unable to consent to voluntary sexual conduct). Other reasons a person may be unable to consent include that the person is asleep, unconscious, ill, under pressure, or under the influence of drugs or alcohol.

Source:

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), UN Women, World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Essential Services for Women and Girls Subject to Violence (Module 1) 10 (2015), http://www.unfpa.org/publications/essential-services-package-women-and-girls-subject-violence

Supported-Decision Making

Supported-decision making are mechanisms to support people with disabilities who require assistance to make decisions independently and retain legal authority to make decisions. Supported decision-making systems come in various forms, such as informal circles of support or formal support networks. No matter the form, they must prioritize a person’s choices and desires and protect that person’s legal rights.

Supported-decision making is an alternative to decision-making models that formally substitute another person’s decision for the person with the disability. Substituted decision-making models perpetuate power imbalances, which can make women and young people with disabilities especially vulnerable to gender-based violence and other forms of abuse and ill-treatment.

In the United States of America, the Center for Public Representation and Nonotuck Resource Associates developed a pilot project for supported decision-making. Beginning with nine adults with intellectual or developmental disabilities, the project proved very successful, with the participants using supported decision-making for seventy-two decisions in the first two years. The model developed by the Center for Public Representation and Nonotuck involves four components: “(1) Individuals with [intellectual or developmental disabilities] enter into Representation Agreements in which they specify areas where they need help making decisions and designate supporters to help them reach their decisions. (2) Support areas include healthcare, finances, employment, living arrangements and relationships. (3) Network supporters, who sign statements that they will respect the person’s choices and decisions, can be family members, friends, and past and current providers. (4) Individuals sign their Representation Agreements before a notary public who stamps, signs, and dates the document, making it official, and hopefully, a document that will be honored in the community by doctors, merchants, landlords, etc.”

Sources:

CRPD Committee, General Comment No. 1 (2014) Article 12: Equality Recognition Before the Law, para. 29, U.N. Doc. CRPD/C/GC/1 (May 19, 2014)

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), Thematic Study on the Issue of Violence Against Women and Girls and Disability, para. 16, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/20/5 (Mar. 30 2012). http://www2.ohchr.org/english/issues/women/docs/A.HRC.20.5.pdf

Ctr. for Public Representation and Nonotuck Resource Assocs. Inc., Pilot Project: The Supported Decision-Making Pilot Project, Supported Decision Making Pilot Project (2017), http:// supporteddecisions.org/pilot-project/

Survivor-Centered Services

Survivor-centred services are those that “prioritize the rights, needs, dignity and choices of the survivor—including the survivor’s choice as to whether or not to access legal and judicial services”.

Source:

Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), Guidelines for Integrating Gender-based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Action: Reducing Risk, Promoting Resilience and Aiding Recovery 252 (Aug. 2015), https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/system/files/2015-iasc-gender-based-violence-guidelines_lo-res.pdf

The Right to be Free from GBV

The Right to be Free from GBV references a range of fundamental rights protected in international and regional human rights treaties, including the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), which underpin the right of people with disabilities to be free from gender-based violence.

These include the rights to:

- Freedom from gender-based violence.

- Life.

- Liberty and security of the person.

- Equality and non-discrimination.

- Accessibility.

- Freedom from torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

- Physical and psychological recovery, rehabilitation, and social reintegration of victims of violence, abuse, or exploitation.

- Consent to marriage and equal rights within marriage.

- Freedom from harmful practices.

- Equality before the law and access to justice.

- Adequate standard of living and social protection.

- Protection and safety for people with disabilities in situations of risk.

- Live independently and be included in the community.

Sources:

Twin-Track Approach

Twin-track approach refers to addressing disability inclusion through:

- systematic mainstreaming and

- “targeted and monitored action aimed specifically at [people] with disabilities”

For example, a rape crisis center that is available and accessible to all but has programming for women with disabilities including trained counselors and support groups for women with disabilities only.

The Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities has explained that the twin-track approach refers to a State’s obligation to: “systematically mainstreaming the interests and rights of women and girls with disabilities across all national action plans, strategies and policies concerning women, childhood and disability, as well as in sectoral plans concerning, for example, gender equality, health, violence, education, political participation, employment, access to justice and social protection” and “targeted and monitored action aimed specifically at women with disabilities”.

Source:

Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD Committee), General Comment No. 3 (2016) Article 6: Women and Girls with Disabilities, para. 27, U.N. Doc. CRPD/C/GC/3 (Nov. 25, 2016).

A glossary is a list of words and their meanings. This glossary is for young people with disabilities.

Gender-Based Violence (GBV)

Violence is when people might hurt you or do bad things to you.

Violence could be many things like:

- Someone hurting your body

- Someone forcing you to have sex or do sexual things

- Someone stopping you from getting the things you need.

Like support, food, medicine, money or wheelchairs

Sometimes we call violence Gender-based violence.

It can happen to anyone.

But it usually happens to women and girls.

Everyone has the right to be safe from violence.

People with disabilities have the right to:

- Be safe from violence.

- Get the right help from the police, courts and other services.

Governments must make sure that:

- No one in the government is violent to people with disabilities.

This includes the police and other people who work for the government.

No one else is violent to people with disabilities.

This includes parents, boyfriends and girlfriends and people who support people with disabilities.

People with disabilities get good support and information if violence happens to them.

The support and information should be right for them.

Services and information are easy for people with disabilities to use.

For example, health services and places that keep people safe from violence.

Governments must make sure that:

There are good laws, plans and rules to keep people with disabilities safe from violence.

For example, it must be against the law to stop women with disabilities having children unless they agree to it.

Governments must make sure that:

People with disabilities can have a say in the laws, plans and rules.

Governments must make sure that:

People do not think bad things or have wrong ideas about people with disabilities.

Governments must make sure that:

People in the community do not hurt people with disabilities.

For example, they should not force women and girls to get married.

Governments must make sure that:

People have training about how to support people with disabilities who experience violence.

For example, the police, judges and health and care staff should get training.

Governments must make sure that:

There is good information about violence that happens to people with disabilities.

This will help people make good plans and laws.

Governments must make sure that:

The police and courts take action if violence happens to people with disabilities.

For example, courts should listen to women with disabilities and punish people who hurt them.

Governments must make sure that:

People with disabilities get the right money and support to cope after violence.

If you want to learn more, you can read this document called Information About the Rights of Women and Girls with Disabilities to be Safe from Violence

Legal Capacity

Legal Capacity means a person’s right to make their own choices about their lives.

People with disabilities have the same rights as everyone else.

But people often stop people with disabilities from making their own choices and getting their rights.

Supporting people with disabilities to make their own choices is sometimes called supported decision-making.

All people with disabilities should get support to make their own choices if they need it.

This includes people with disabilities who need more support.

The support might include:

- Information that people with disabilities can understand to help them choose what is best for them

Computers or equipment to help them say what they want

- Someone to support them to think about what they want

Some people with disabilities may find it very hard to make their own choices.

Other people can support them to make choices.

But the support should always be about what people with disabilities want.

It should never be about what someone else wants or thinks is best.

The support should be free or low cost so that people with disabilities can afford it.

People with disabilities should be able to stop or change the support if they want to.

People with disabilities should still get all their rights if they need support to make choices.

For example, they should still be able to get married, have children and vote.

People should get training to help people with disabilities make their own choices.

For example, doctors and people who work in courts, like judges.

Laws and rules that countries make should say that:

- People with disabilities have the same rights as everyone else

- People with disabilities can make their own choices, with support if they need it.

People with disabilities should get information they can understand about their rights.

If you want to learn more, you can read this document called Information About the Rights of Women with Disabilities to Make Their Own Choices about Their Lives

Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR)

Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights means the rights of people to do with their bodies, sex, relationships and giving birth to children.

Everyone has the right to make their own choices about their bodies, health, sex, relationships, and having children.

People with disabilities have the same rights as everyone else.

People with disabilities have the right to:

Be safe and healthy.

For example, to know how to have sex in a safe way and keep safe from other people hurting them.

Be treated fairly and have the same chances as other people.

Decide for themselves about sex, relationships and having children.

For example, decide if they want children and how many to have.

Governments must make sure that people with disabilities get these rights.

If you want to learn more, you can read this document called Information About the Rights of Women and Girls with Disabilities to Do with Their Bodies, Sex, Relationships and Giving Birth to Children [LINK to pdf]